Robert Braczyk: Cardinal Directions

Bob and I had a chance to chat about his current show at Bowery Gallery. I learned that he and I have several things in common– we are both from New England, we both come from a long line of woodworkers, and we both attended Boston University–I also discovered that we both seem to be engaged in a similar investigation in our work…

Eileen Mooney: So what I found to be particularly interesting in your artist statement that related to my work was where you wrote, “The persistence of character suggests to the artist a vocabulary of trees analogous to an alphabet that is the matrix for words and sentences. As letters and syllables are recombined relative to rules of verbal syntax, wooden elements have a physical syntax, a natural structural logic that affects how they can be recombined.” That was really interesting to me.

Robert Braczyk: I think it's true.

Eileen Mooney: I’m wondering if you could say more about that.

Robert Braczyk: I grew up doing woodworking and walking in southern New England through an area referred to as “Drumlin landscape.” For thousands of years as the glaciers advanced and retreated from Worcester south, they scraped out valleys and rounded bedrock hills. I was fascinated because the rock formations push out from under the ground, so there's a sense of things under the surface, moving. Then of course, there's all the trees–the deciduous trees. Particularly when the leaves aren't on you see that lattice of the branches against the sky. It's a certain kind of gesture, a character of form. For years I thought, “what am I doing as a woodworker?” I’m joining pieces of wood to make structures. Then I would look at trees and think, look at those beautiful joints! Nature made joints so elegant and essential. About twenty years ago I was up in Massachusetts for a winter. I was out in the backyard. Everybody has a brush pile in their backyard in New England. If you've got a house with an acre of property you've got someplace to throw branches.

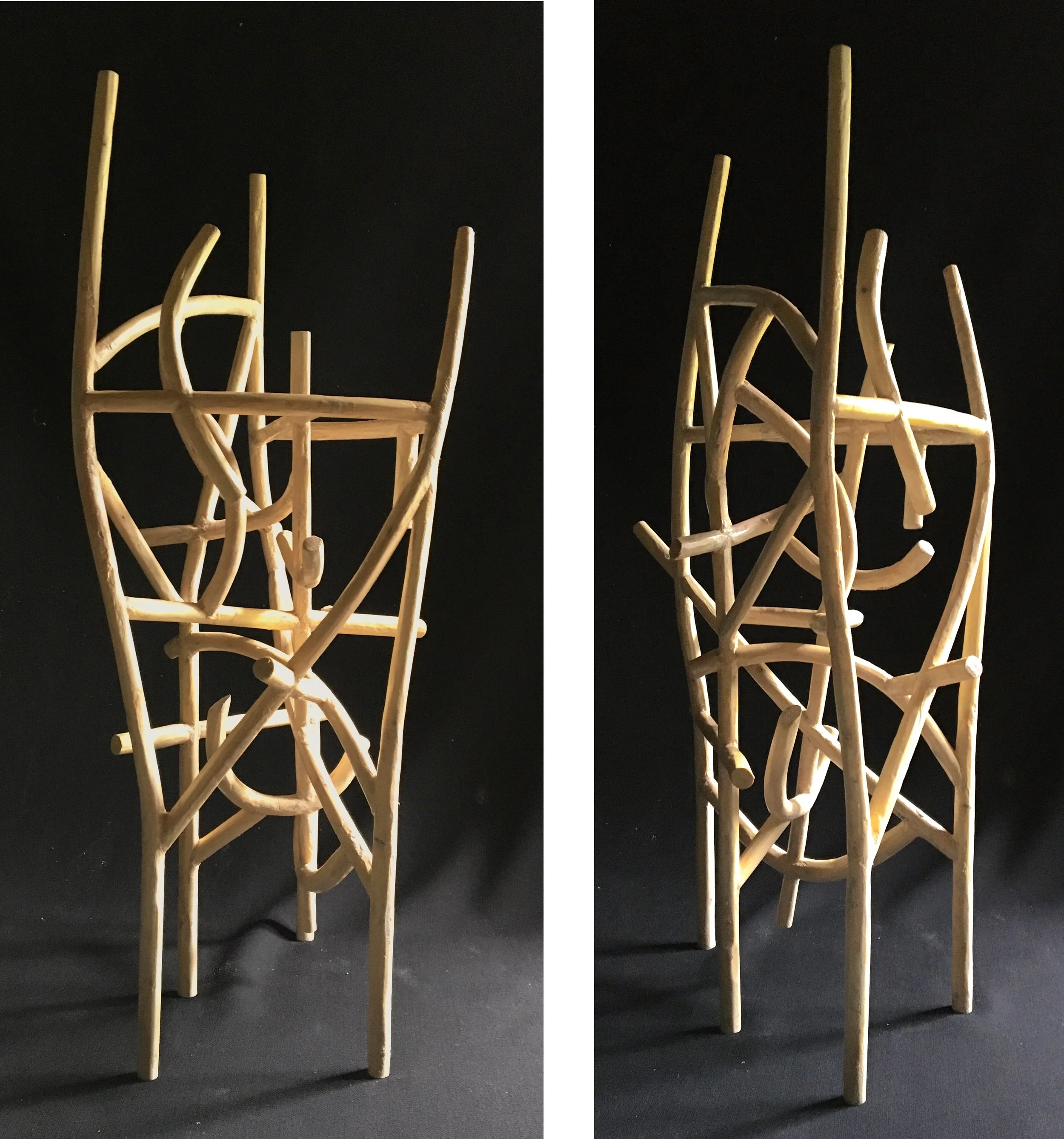

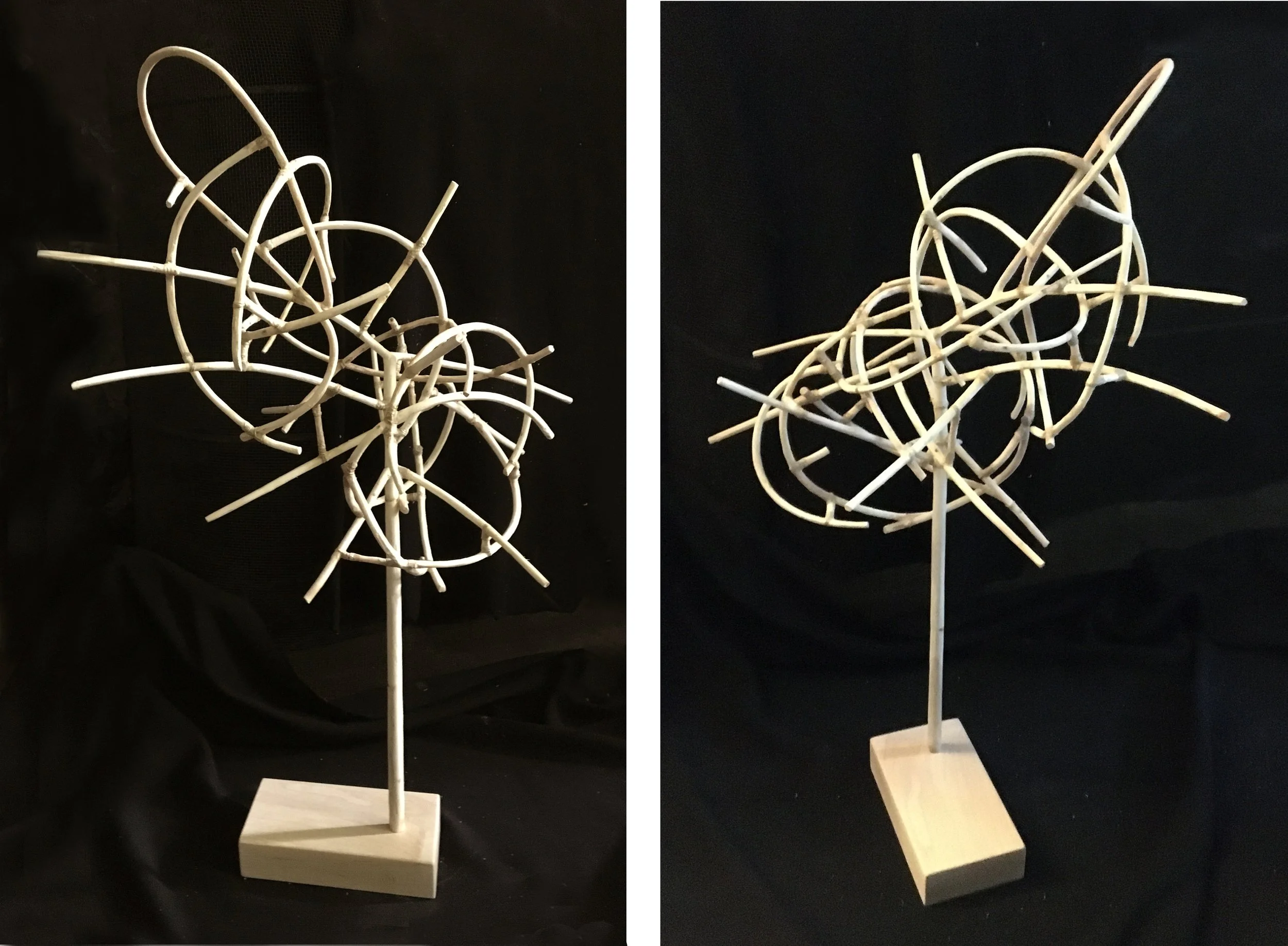

Robert Braczyk, Gestas, Maple, 21 ½ x 7 ½ x 10 inches, 2022

Eileen Mooney: Yes, for sure.

Robert Braczyk: I was out in the back of my parents' house, looking down in the snow. I saw sticks poking up through the white backdrop. I realized there was a certain character in each of branch, truncated in that way. if I cut one in a certain way I would get a fork, or I could sometimes get a T-shape. What you had everywhere were gracefully tapering rods. I just realized a way that I could do something with this. I have thousands of natural elements to work with. I think it was about 2013 or so. You have these hunches about what might work for you, but I'd never acted on it. In that moment I realized that I could see a way forward, so I began to collect the branches. It's a fairly simple process. Just dry them and strip the bark off, and they begin to speak to you. They tell you things. They're very beautiful and I felt that they answer each other. A fork and another branch sit in relationship to each other – they work off of each other. That was the theme of my first show. For a while there, I was laboring with these sticks because I was having trouble making them go horizontally. Then I realized – no, wait a minute, all these trees are telling you that they want to be vertical.

Eileen Mooney: Right!

Robert Braczyk: There is a great deal about vertical in my work. If you walk out in the woods, it's all about verticality. Everything is going upwards. I found that to be the major axis of so many things. It was a natural evolution from my figurative work. My figurative sculptures are mostly standing figures.

Eileen Mooney: Yes, I noticed that.

Robert Braczyk, Dismas, Maple, 21×7×7 inches, 2024

Robert Braczyk: If you're trying to get at the essence of a thing, you try to see it in its most essential utility. For example, it’s easy to imagine a human being standing. That's what has differentiated us from so many other animals, we stood up. everything I tend to look at seems to be a statement about rising up. And so that became a theme of a lot of the work. Then of course, there's the open form aspect of some pieces. My earliest pieces are inspired by Picasso’s welded sculptures and Julio Gonzalez.

Eileen Mooney: I looked him up after I read your artist statement.

Robert Braczyk: Picasso invented welded sculpture.

Eileen Mooney: Oh, I didn't know that.

Robert Braczyk: It was about 1929. Gas welding had been developed in the First World War. Gonzalez was a metalsmith and knew how to weld. Picasso asked him to weld together metal rods as a largely literal interpretation of one of his drawings. Immediately someone, said, “Oh, it's drawing in space.”

Eileen Mooney: Wow, I never thought of it that way. Yes, it really is.

Robert Braczyk: It was a new kind of sculpture. For 100,000 years human beings had been making sculptures, but they were almost all figures. The subject of sculpture was the compact human form, and then Picasso comes along with another view of things.

Eileen Mooney: I never knew that.

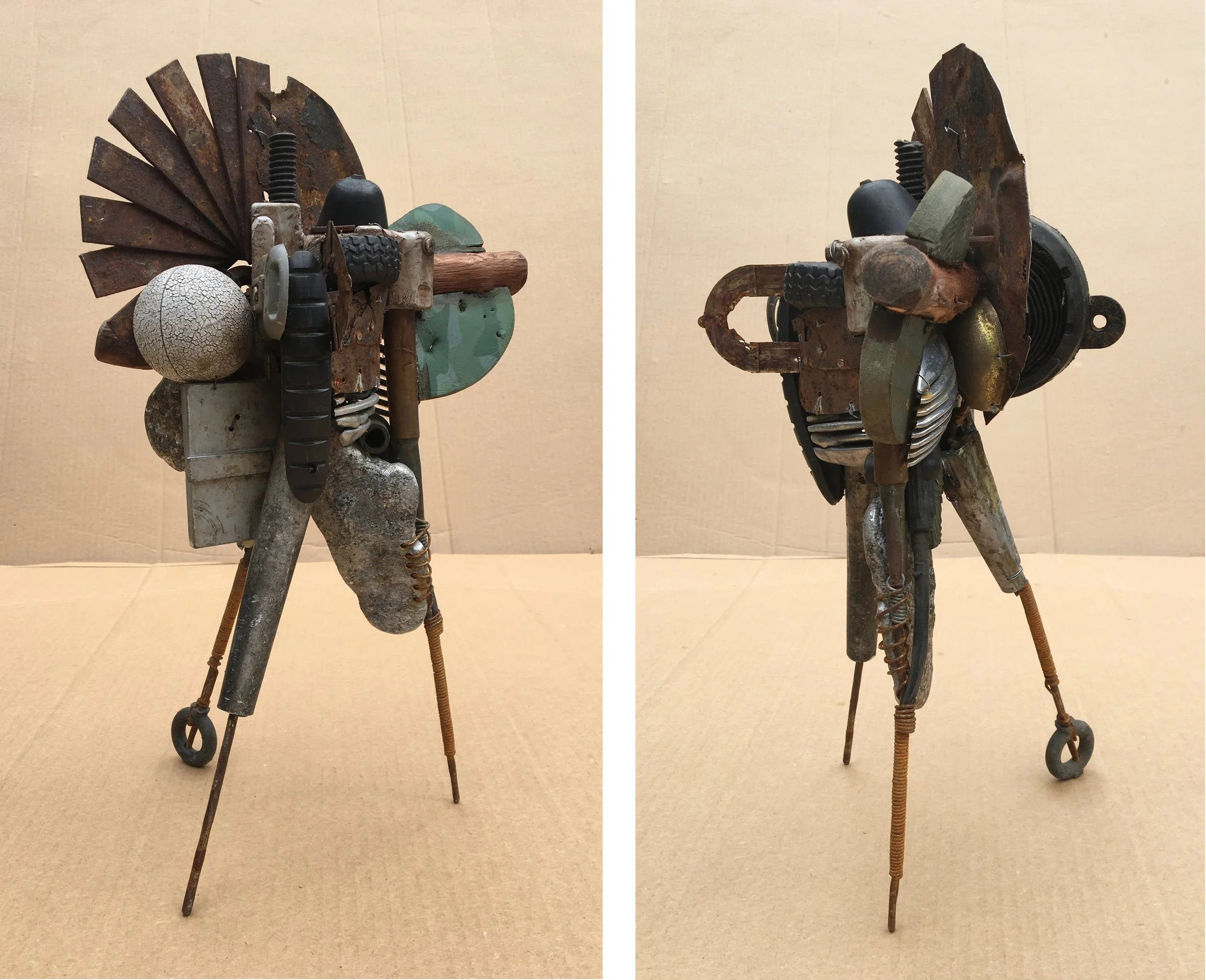

Robert Braczyk, Roadside Attraction, Mixed Media, 16 ½ x 9 ½ x 8 ¾ 2024

Robert Braczyk: For this coming show I'm beginning to sense that the clay modeler, the figure modeler that I was trained as and worked at for 25 years, is coming back. The most profound insight that I gained as a figure modeler was that believable form expands from the inside out – your head, your thumb. If you consider it, you realize nature is building out from the inside, pushing everything out. Growing. Successful form is form that has a sense of expanding. I think I see that in those oil drawings of the numbers that you're doing. I feel the form expanding from the inside out. That's organic form. That character of form is the core of what that kind of sculpture is about. And so that very attractive aspect is creeping back in the work. The idea is that the form is coming out of a center, a core, an axis. That's a very important thing that has happened recently in the work. I don't know where it will lead. Then too, I might go back to the more open form work. For me, one of the great inspirations is the Windsor Chair. Do you know the Windsor Chair?

Eileen Mooney: Yes, I do.

Robert Braczyk: If you can make the joints in a Windsor chair, you could build my sculpture.

Robert Braczyk, Graffiti III, Maple, 23 1/8 × 6 ½ x 5 inches, 2021

Eileen Mooney: How so?

Robert Braczyk: Everything is based on that idea of joining and the kind of space a chair creates, the kind of space an object like a chair occupies, structurally solid and at the same time mostly empty. Another concept that has crept into my thinking is that so much of the art that we know of, we know from photographs.

Eileen Mooney: Yes. Absolutely.

Robert Braczyk: Further, I think our culture is losing a lot of sensitivity to three-dimensional space.

Eileen Mooney: Oh…I agree.

Robert Braczyk: Yes. So, in another sense, this work is the antithesis of digital imagery. It's hands-on, three-dimensional sculpture.

Eileen Mooney: Okay, I love listening to you talk, and as you were talking, I pulled up your website, and so I'm looking at Sculpture 24-25. I'm seeing the first image, Nexus. How would you describe this for me, in terms of joining?

Robert Braczyk, Nexus, Maple, 25 ¼ x 7 ¾ x 7 inches, 2025

Robert Braczyk: The elements are attached with dowels and screws and since they are rounded, they mirror the parts of a Windsor chair. I also use triangular construction whenever I can. Most components have at least two points of contact. There is always an awareness of the vertical and horizontal as there is in any chair.

Eileen Mooney: Yeah.

Robert Braczyk: Those oil drawings that you did with the numbers have a vertical and a horizontal in them.

Eileen Mooney: Yes, they absolutely do.

Robert Braczyk: When Guston was working in Italy, in the 50’s, he did a drawing looking down a road in one-point perspective, toward a village. At the point of convergence there is a crossroad, so another road meets it at a right angle, that is to say horizontally. It's just a little sketch. Its motif is that it rises, then it hits the horizon, and it spreads the space out in that direction. I think he was Influenced by that essential notion of horizontal and vertical. Sounds simple but that insight is the organizing principal of so much of western art.

Eileen Mooney: If we could just go back–what I found so interesting about what you said in your artist statement–the vocabulary, or the alphabet of these tree forms. Maybe not literally alphabetic, but that there are these structures and that you're putting together these structures in this way that sometimes I think that in my work, as I'm putting together the numerals and the alphabetic characters. I almost feel like sometimes I'm looking for some kind of essential form as I'm putting them together. Does that make sense? Like, something that can be abstracted from these forms–that really already are abstract, you know? What you said in that paragraph really resonated with me for that reason, because it almost feels like you're sort of saying something essential of the trees.

Robert Braczyk: It's about structure, “the relationship of the parts to the whole”. That's the first definition of structure in the dictionary. In essence it's not more complicated. Everything is structured, and nothing happens until you have one form or one aspect opposed to another. They begin a dialogue. The complexity of the dialogue that an artist is able to construct can be very attractive to a viewer. I intend my pieces to be attractive and seeing logical relationships is pleasing. We relate to symmetrical faces. Beautiful people have symmetrical faces. Though we may not think it out loud or notice. There's something very profound, and I think some of the other people that you interviewed in this blog were getting at the same thing, which is that there's an organic structure that, if you just keep reducing it, and going back as far as you can, almost in a scientific way, you realize that there's a unity of all form. For example, animal growth begins when a cell divides in half. There's symmetry in our very beginning.

Robert Braczyk, Cell, Maple, 24 × 11 ¼ x 7 inches, 2024

Eileen Mooney: Yes.

Robert Braczyk: It's part of the vibration of our chemistry, and the physics that govern the structure of atoms and molecules. Cells split down the middle, and they become symmetrical. That's the core of what I address when I go into the studio each day. There's going to be elements. I'm going to lift them up into space as best I can. Try to keep them from looking labored, and understand the structure that they require in order to sit in relationship to each other. I like to keep it as open and work as fast as I can, but it is sculpture, so it's not that fluid. I can't change things that easily. I have to make each form and pose them against another. What I'm constantly trying to do is to find out how one form answers another, and how does it sit in space relative to that other. The phrase that I came across recently is that when a work of art is finished, when it really works, it has an “innate sense of authority”.

Eileen Mooney: Yep.

Robert Braczyk: And that's what we all struggle for. We were in Florence with our teenage daughters during a heat wave. There were tourists everywhere, and we went into the Academia to see the Michaelangelo’s and got swallowed in the crowd. We staggered out of the ticket area and came into the arcade that led straight back to where The David is. And my oldest daughter, all of us really, took two steps, and then I saw her do a double take. It wasn't just that it was a famous sculpture, the thing arrested her, it stopped us all the same way in the same moment, really. That sculpture projects an immediate sense of authority, something that human beings can identify in a flash. It's not just a decorative thing. It's something that's very human. It's like when people get along – when you hit it off in conversation with somebody. You feel their humanity. And that's what I struggle for, that's my modus operandi in the studio. That's what I'm looking for every day. And of course, it doesn't happen every day, but it's an ideal.

Eileen Mooney: In graduate school, we used to call it “inevitability.” Like, when a piece hits it, Margaret (Grimes) used to say that it has an inevitability to it, like, of course–it must be this way–this painting was always going to happen.

Robert Braczyk: It has to be that way. It can't be any other. In a Cezanne painting there are perhaps two thousand brush strokes on the canvas but when you look at it you say, “No–I wouldn't change a thing. Every stroke feels like it belongs where it's supposed to be.”

Eileen Mooney: Right.

Robert Braczyk: Of course a lot of my perceptions come from sculpture. As you are making objects there is an awareness that nature builds in a similar way. Life’s energy pushes out when you are modeling portraits. When you crack it and you figure the process out, you get a sense of life. You feel like you are in the presence of life.

Eileen Mooney: Yeah.

Robert Braczyk: It’s important to talk about the work. I welcome talking with you. We want to share these things with people that we know have a common understanding on the issues.

Eileen Mooney: It's critical, I think. I feel like I learn so much every time I do an interview or write a blog post, but apart from that, getting an opportunity to talk to another artist and listening to them talking about their work, just hearing some of these things that you're saying is just…reassuring, you know?

Robert Braczyk: Yes. I was just reading something by Elaine de Kooning. She said, “You know, you can work alone in the studio for a long time, but you really should talk to somebody once in a while.” The other thing that I'm fascinated about is that sculpture is a kind of communication that can't be made known in any other way.

Eileen Mooney: Yes!

Robert Braczyk, Accretion, Maple, 25 × 13 ×16 inches, 2023

Robert Braczyk: If you can put it another way there wouldn't be any need for making a sculpture or painting a painting. Making sculpture, making any visual art is not about words. When you were talking about the language, the vocabulary of trees, the way I choose to communicate that is with tree elements. That is the point of the work. What do those tree parts need in order to express themselves? You can't say it any other way. You can't tell somebody what dance is unless they see a dance.

Eileen Mooney: Yes.

Robert Braczyk: An art form exists because there's no other way to communicate that particular thing. It's the simplest way I can say it.

Eileen Mooney: I completely agree with you.

Robert Braczyk’s show, Cardinal Directions, is on view at Bowery Gallery from January 27 through February 21, 2026. The opening reception is Thursday, January 29 from 5-8pm, and gallery talk on Saturday, February 14, from 3-4pm.