Stephanie Franks: Kind of Blue

Stephanie and I engaged in many back and forth emails about what we we do for the blog post for her current show, Kind of Blue, at Bowery Gallery. I wanted to interview her, and having just come off of interviewing Rachel Siporin in her studio space in South Glastonbury, CT, and then having interviewed Ruth Miller and Joseph Byrne in their studio spaces (also both in Connecticut), I wanted to interview Stephanie in the same way. Sadly, that was not possible this go around. Due to our extremely busy lives, it was difficult to sit down and engage in a real-time zoom interview. However, we did engage in several back and forths over email about her work. She very generously shared with me some of the “pre-writing” that she wrote to prepare her press release and from there, as always, I had questions and ideas. I had ideas about this blog post that were just a tad too big for me to fully realize in the month of October, which is potentially the busiest month of the year at my school. Fortunately, the questions I had were just an email away, and Stephanie very generously wrote thorough responses (though maybe she does not think that she did). She also provided me with images of her work that show her iterative process. While many artists often take paintings out and continue to work on them after years of leaving them alone, she also does this with her drawings. I first learned of this from reading her Instagram posts, and for some reason, felt surprised to hear her say that she is reworking a drawing from five to ten years ago (or more). I felt the same way about her devotion to transcription and looking at what she has shared with those, as well. On a personal level, looking at her work and reading the text in her posts has been an important lesson for me, which might be an idea that is not fully formed, but has to do with the idea that one’s works do not have to be confined to the timeline of the chronological file of works made—and this extends to art history with her commitment to the transcriptions. It’s liberating.

With all of that said, here is what has materialized to be an interview-via-email, which consists only of three-ish questions on the face of it, and images that hopefully demonstrate her process.

Stephanie Franks, "Green Bottle", Oil on Canvas, 36" x 36", 2025.

Eileen: You shared with me some notes on your work to prepare for writing your press release. One part that I found particularly interesting was when you wrote,

Strong composition, within the container of the rectangle or square I am working within, is essential to what is important to me. This should be particularly evident in my black and white drawings, which emphatically revolve around a search for strong composition and within that, a sense of spatiality–which is to say, an expansive and elastic space in direct relation to the compressed space of the rectangle, and ultimately to wind up with a poetry of space. The edges of a given composition are seriously considered as I figure out how to create a container of space that is unified and works as a whole.

Wow. Right there in this little quote, there is so much to ask about. I have two questions. The first one, is regarding something I have observed about the consistency that I see across many of your compositions, and I think this quote brings this observation to mind. Can you talk more about the emptiness of your centers in contrast to the collection of forms around your edges? Second, and maybe this is related to this center-to-edge dialectic, can you say more about what you mean by "expansive and elastic space"?

Steffi: Honestly it is a bit of a puzzle to me why oftentimes the centers are "empty" and the edges are where the action often takes place. I don't think there is a simple answer but I will throw out some thoughts. In my work, I often erase out/clear out what seems like extraneous elements/stuff in search of coherence. My personal sense of aesthetics was influenced from an early age by mid 20th Century Modernism, related, I would say, to the house we lived in longer than any other house (of many) from my childhood. The house, in Los Angeles, was a beautiful example of mid-century Modernist architecture and I had a particular affection for that house. I think it formed in me a penchant towards geometry and to some degree, minimalism.

Stephanie Franks, "Open Book", Oil on Canvas, 30" x 22", 2025.

As a student of Nick Carone (who had been a student of Hans Hofmann), I became very interested in the lessons of activating the entire picture plane, which absolutely included an awareness of not just the relationship of the parts to each other but also the parts to the entire rectangle that we were working on. Nick talked to me a lot about "the rectangle,” and that meant bringing things out to the edges of the rectangle we worked on. There was also an emphasis on the contradiction and tension between affirming the two dimensionality of the rectangle in opposition to the articulation of the three dimensional space we were observing and drawing from in his class. In my drawings especially, the elasticity comes from the very alive and dynamic tension between that flatness and the three dimensional space. It remains somewhat of a mystery to me to this day because I can draw and draw and draw and not be able to figure out how to achieve that tension and not even know I am not achieving it, until I do, and when I do, I know it. That is what keeps it exciting for me–the fact that it remains a challenge. It is very hard to explain, actually, what "elasticity" means and what I have said probably only touches the surface. Expansiveness is similarly mysterious to me and also I sometimes don't even recognize that I don't have it when I don't have it, but when I get it, I know it. In a drawing, it allows for intervals of space to circulate throughout; it allows the work to breathe and pulsate.

Stephanie Franks, “Chautauqua Interior With Clamp Light”, Charcoal on Paper, 30x22 inches 2015-25.

When I paint, I have to admit, the color takes over. I am not sure I have been able to pull together the issues that compel me in my drawings (discussed above) with the way I use color. I am still trying to figure that one out. I feel like I have a direct line to color and always have. In other words, my relationship with color is not so much learned as it is innate. Once color gets into my hands, it pretty much leads the way. That is not without attention to composition, however, which is always extremely important. I work intuitively on all of it, however: the drawings, collages, and paintings. That said, and probably of some importance, with painting, I often start from something observed. It might be a still life in an interior or an interior/exterior view or a transcription. Then I use elements of the structure of what I am looking at and bring them into the painting (also I do this in my drawings). Structure is tantamount to the way I work. I construct my drawings and paintings. In the drawings, I usually sustain my response to what I am looking at (still life, master work, etc) and go back and forth between the structure of what I am looking at vs. the invention of a structure that builds as the work builds. I do this more or less in my paintings, too, but sometimes my paintings veer quite far from the original observed source. And sometimes they continue in close response to the observed source. I construct my collages in a different way. They are not from observation of anything in particular and they get constructed as paper on paper on paper, using cut and torn and painted papers, and color aid and remnants of cut pieces, etc. The constructing is the physical constructing of the piece. Sometimes there can be many layers upon layers.

Stephanie Franks, “Horseshoe Bay", Collage, 10" x 6", 2023.

But to return to the original point about the margins–bringing things out to the edges calls attention to the boundaries of the rectangle and can bring a sense of presence of what is outside those edges, or what is outside that world that is inside the rectangle. Opposing forces inside the rectangle and thrusting out towards the edges can also give a greater muscularity to the work. I don't, however, think of my collages and paintings these days as muscular in a way that I think I aspired to when I was younger (probably because I am so much less so, haha).

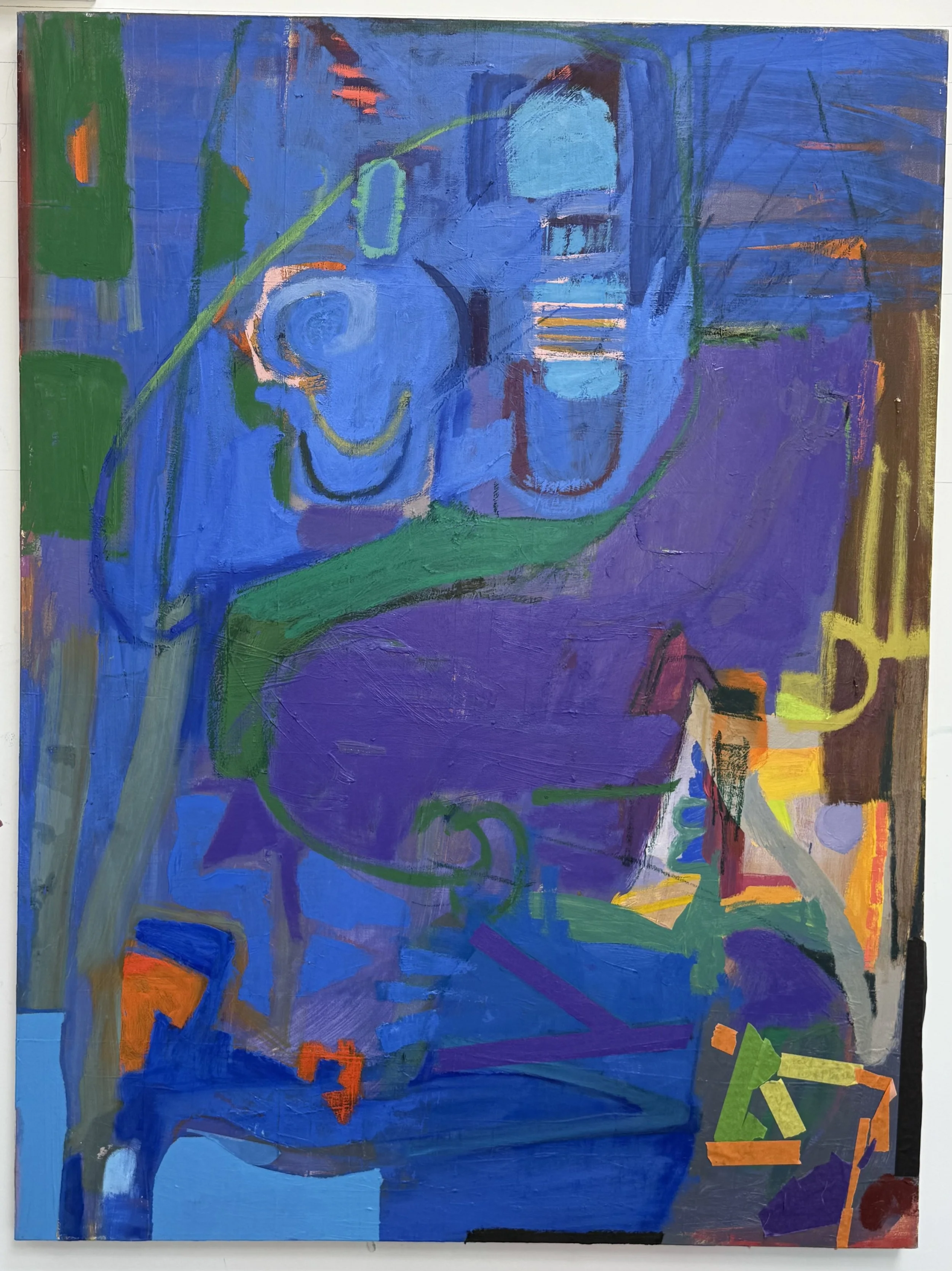

Stephanie Franks, "Let They Spirit Soar", Acrylic/Oil on canvas, 48" x 36", 2021.

Apart from my liking for big open spaces in my paintings (and my environment, and nature), one more thing about having activity in the margins (because I have wondered why I do this) occurs to me. As a child, I grew up with a bigger than life, very unstable, severely bipolar mom. When she was good she was great; when she was bad, she was off the charts bad. Her dramas consumed me and others in my family in different ways. I think for me, it seemed best to stay in the margins as much as possible and not make a stir. Bubbling inside of me was a lot of life. While I surely wanted attention, I operated so as to divert the attention away from myself. So perhaps the activity at the margins is in some way reflective of that. I am not really sure.

Also quite simply, I like asymmetry.

Eileen: With one or two exceptions, I find it difficult to tell the difference between your purely abstract and your more representational work. You so eloquently wrote,

...But the paintings, the drawings, the collages, the transcriptions, figurative, abstract or somewhere in between, all come together as one. It is like many branches coming out of but also coalescing at a central tree trunk or a circling spiral that eventually hones in on a single spot. While investigating from different vantage points, it all eventually comes together at a natural meeting place or center.

I, myself, am an artist who operates in abstraction/invention and from perception, and I am transferring my experience painting from observation to my more abstract inventions in intentional ways, and perhaps also in more covert ways. For me and my work, these two things still feel like separate paradigms. When I look at your work, there is minimal separation. It feels as though you are fundamentally focused on compositions--no matter what the initial stimulus may be--imagined and generative abstraction, representational, or from transcription. But I suppose that I am wondering about your awareness of how you transfer your experiences in those three types of work. Can you speak to that, and maybe reference a few pieces from the show?

Stephanie: I find it hard to separate the work into three paradigms because in the end, the same forces in me drive all of them. Perhaps at the beginning of a transcription, I am trying hard to stay more or less close to the thing I look at in order to learn from it and in learning from it, I can then stray free from it, or not.

For me, good representational art is also strong abstractly. I have always felt awkward when it comes to trying to draw or paint something to look like what it actually looks like. I am not and have never been that kind of artist. Somehow though, by concentrating on structures, composition, relationships, rhythms, color, the lusciousness of paint, etc., it has given me a way to transpose what I am looking at into a language that reads as more or less abstract, sometimes with recognizable elements. I might start a work with those familiar objects or structures and somehow the work itself demands I stay on that path of preserving that familiarity to a degree while also hopefully inventing as I go.

Or I might start out with those recognizable elements and then the work demands more and more that I eliminate that which is recognizable for the sake of the whole. It is maybe like hitting different forks in the road in different paintings, so in one painting I choose the fork that stays more with the path of representation; in another painting, I take a different fork and I allow myself to just let the color and the painting process itself lead the way. Quite often, recognizable shapes (often bottle or vase shapes for reasons not clear to me) will then suggest themselves to me and I tease them out and bring them to the surface (as in the painting in my show, "Green Bottle", or the strange object/figure-like configuration semi-surrounded by red lines towards the bottom of the painting, "Memories of Herculaneum", or the little painting called "Blue Bottle", which somehow managed to have a bottle coming out of the edge and a green and orange cup on the left near the bottom, and the little vessel with plant forms coming out of it at the bottom right in the painting, "one Red Stripe”) .

[Here are three iterations of Memories of Herculaneum, which I asked Stephanie for in order to show the iterative process in her work.]

Sometimes I tease them out and cover them up again and you may see them as pentimenti or not. "Afterglow," from the Matisse, came out of me obliterating, out of frustration, what I had put down, which was too close to the Matisse for me and therefore kind of boring. In the process of obliterating, the painting started to get interesting and I left it in a state which intrigued me. "Barn Drawing" and "Still Life with Plants" are two drawings in the show, by the way, that started from observation and to some extent stay true to certain of the observed structures, spaces, objects, but also allowed for reinvention. I need to reinvent at times to make things interesting. More and more, I also allow objects to suggest themselves to me, that might at first be barely peeking out from under layers of medium.

Composition, as you insightfully point out, is very fundamental to me. The process totally dictates where the work goes and I generally allow my work to freely go where they take me, within certain bounds. Lastly, I think the hardest thing for me is knowing when something is finished. Sometimes, I absolutely know. Other times, I may leave something open ended or think something is finished and then a year later take it out and realize, nope, its not, and then I may know exactly what it needs…or not.

Stephanie Franks, “After the Song is Sung”, Oil on Board, 16×20 inches, 2021-25.

Stephanie Frank’s outstanding show, Kind of Blue, is currently on view at Bowery Gallery from October 28-November 22, 2025.

-ebm.